While the VB theory, to a larger extent, explains the formation, structures and magnetic behaviour of coordination compounds, it suffers from the following shortcomings:

(i) It involves a number of assumptions.

(ii) It does not give quantitative interpretation of magnetic data.

(iii) It does not explain the colour exhibited by coordination compounds.

(iv) It does not give a quantitative interpretation of the thermodynamic or kinetic stabilities of coordination compounds.

(v) It does not make exact predictions regarding the tetrahedral and square planar structures of 4-coordinate complexes.

The crystal field theory (CFT) is an electrostatic model which considers the metal-ligand bond to be ionic arising purely from electrostatic interactions between the metal ion and the ligand. Ligands are treated as point charges in case of anions or point dipoles in case of neutral molecules. The five d orbitals in an isolated gaseous metal atom/ion have same energy, i.e., they are degenerate. This degeneracy is maintained if a spherically symmetrical field of negative charges surrounds the metal atom/ion. However, when this negative field is due to ligands (either anions or the negative ends of dipolar molecules like NH3 and H2O) in a complex, it becomes asymmetrical and the degeneracy of the d orbitals is lifted. It results in splitting of the d orbitals. The pattern of splitting depends upon the nature of the crystal field. Let us explain this splitting in different crystal fields.

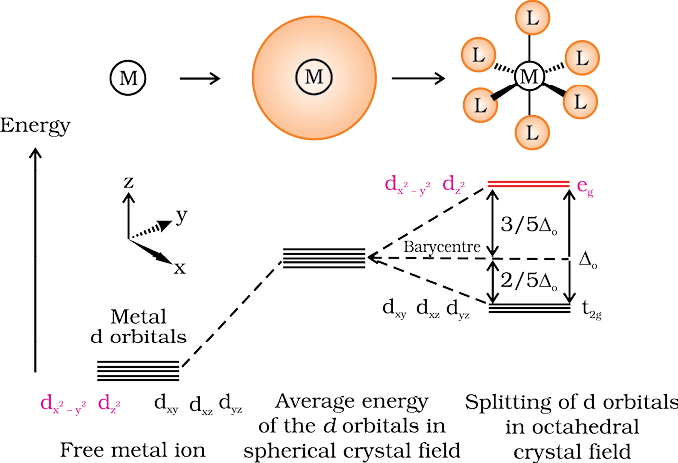

(a) Crystal field splitting in octahedral coordination entities

In an octahedral coordination entity with six ligands surrounding the metal atom/ion, there will be repulsion between the electrons in metal d orbitals and the electrons (or negative charges) of the ligands. Such a repulsion is more when the metal d orbital is directed towards the ligand than when it is away from the ligand. Thus, the and orbitals which point towards the axes along the direction of the ligand will experience more repulsion and will be raised in energy; and the dxy, dyz and dxz orbitals which are directed between the axes will be lowered in energy relative to the average energy in the spherical crystal field. Thus, the degeneracy of the d orbitals has been removed due to ligand electron-metal electron repulsions in the octahedral complex to yield three orbitals of lower energy, t2g set and two orbitals of higher energy, eg set. This splitting of the degenerate levels due to the presence of ligands in a definite geometry is termed as crystal field splitting and the energy separation is denoted by ∆o (the subscript o is for octahedral) (Fig.9.8). Thus, the energy of the two eg orbitals will increase by (3/5) ∆o and that of the three t2g will decrease by (2/5)∆o.

Fig.9.8: d orbital splitting in an octahedral crystal field

The crystal field splitting, ∆o, depends upon the field produced by the ligand and charge on the metal ion. Some ligands are able to produce strong fields in which case, the splitting will be large whereas others produce weak fields and consequently result in small splitting of d orbitals. In general, ligands can be arranged in a series in the order of increasing field strength as given below:

I– < Br– < SCN– < Cl– < S2– < F– < OH– < C2O42– < H2O < NCS– < edta4– < NH3 < en < CN– < CO

Such a series is termed as spectrochemical series. It is an experimentally determined series based on the absorption of light by complexes with different ligands. Let us assign electrons in the d orbitals of metal ion in octahedral coordination entities. Obviously, the single d electron occupies one of the lower energy t2g orbitals. In d2 and d3 coordination entities, the d electrons occupy the t2g orbitals singly in accordance with the Hund’s rule. For d4 ions, two possible patterns of electron distribution arise: (i) the fourth electron could either enter the t2g level and pair with an existing electron, or (ii) it could avoid paying the price of the pairing energy by occupying the eg level. Which of these possibilities occurs, depends on the relative magnitude of the crystal field splitting, ∆o and the pairing energy, P (P represents the energy required for electron pairing in a single orbital). The two options are:

(i) If ∆o < P, the fourth electron enters one of the eg orbitals giving the configuration  . Ligands for which ∆o < P are known as weak field ligands and form high spin complexes.

. Ligands for which ∆o < P are known as weak field ligands and form high spin complexes.

(ii) If ∆o > P, it becomes more energetically favourable for the fourth electron to occupy a t2g orbital with configuration t2g4eg0. Ligands which produce this effect are known as strong field ligands and form low spin complexes.

Calculations show that d4 to d7 coordination entities are more stable for strong field as compared to weak field cases.

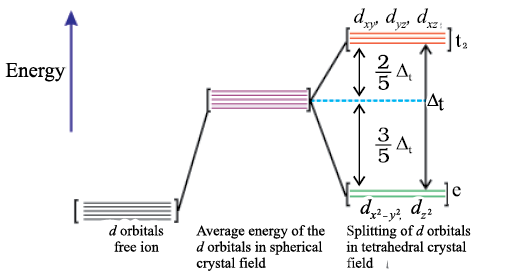

(b) Crystal field splitting in tetrahedral coordination entities

In tetrahedral coordination entity formation, the d orbital splitting (Fig. 9.9) is inverted and is smaller as compared to the octahedral field splitting. For the same metal, the same ligands and metal-ligand distances, it can be shown that ∆t = (4/9) ∆0. Consequently, the orbital splitting energies are not sufficiently large for forcing pairing and, therefore, low spin configurations are rarely observed. The ‘g’ subscript is used for the octahedral and square planar complexes which have centre of symmetry. Since tetrahedral complexes lack symmetry, ‘g’ subscript is not used with energy levels.

Fig.9.9: d orbital splitting in a tetrahedral crystal field.