We will now consider, in greater detail, the motion of a charge moving in a magnetic field. We have learnt in Mechanics (see Class XI book, Chapter 6) that a force on a particle does work if the force has a component along (or opposed to) the direction of motion of the particle. In the case of motion of a charge in a magnetic field, the magnetic force is perpendicular to the velocity of the particle. So no work is done and no change in the magnitude of the velocity is produced (though the direction of momentum may be changed). [Notice that this is unlike the force due to an electric field, qE, which can have a component parallel (or antiparallel) to motion and thus can transfer energy in addition to momentum.]

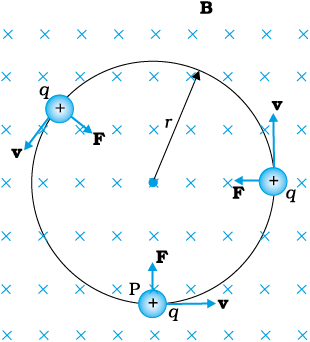

Figure 4.5 Circular motion

We shall consider motion of a charged particle in a uniform magnetic field. First consider the case of v perpendicular to B. The perpendicular force, q v × B, acts as a centripetal force and produces a circular motion perpendicular to the magnetic field. The particle will describe a circle if v and B are perpendicular to each other (Fig. 4.5).

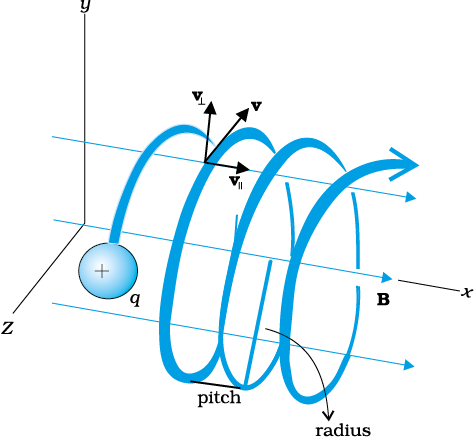

If velocity has a component along B, this component remains unchanged as the motion along the magnetic field will not be affected by the magnetic field. The motion in a plane perpendicular to B is as before a circular one, thereby producing a helical motion (Fig. 4.6).

Figure 4.6 Helical motion

You have already learnt in earlier classes (See Class XI, Chapter 4) that if r is the radius of the circular path of a particle, then a force of m v2 / r, acts perpendicular to the path towards the centre of the circle, and is called the centripetal force. If the velocity v is perpendicular to the magnetic field B, the magnetic force is perpendicular to both v and B and acts like a centripetal force. It has a magnitude q v B. Equating the two expressions for centripetal force,

m v2/r = q v B, which gives

r = m v / qB (4.5)

for the radius of the circle described by the charged particle. The larger the momentum, the larger is the radius and bigger the circle described. If ω is the angular frequency, then v = ω r. So,

ω = 2π ν = q B/ m [4.6(a)]

which is independent of the velocity or energy . Here ν is the frequency of rotation. The independence of ν from energy has important application in the design of a cyclotron (see Section 4.4.2).

The time taken for one revolution is T= 2π/ω ≡ 1/ν. If there is a component of the velocity parallel to the magnetic field (denoted by v||), it will make the particle move along the field and the path of the particle would be a helical one (Fig. 4.6). The distance moved along the magnetic field in one rotation is called pitch p. Using Eq. [4.6 (a)], we have

p = v||T = 2πm v|| / q B [4.6(b)]

The radius of the circular component of motion is called the radius of the helix.

Example 4.3 What is the radius of the path of an electron (mass 9 × 10-31 kg and charge 1.6 × 10–19 C) moving at a speed of 3 ×107 m/s in a magnetic field of 6 × 10–4 T perpendicular to it? What is its frequency? Calculate its energy in keV. ( 1 eV = 1.6 × 10–19 J).

Solution Using Eq. (4.5) we find

r = m v / (qB) = 9 ×10-31 kg × 3 × 107 m s–1 / ( 1.6 × 10–19 C × 6 × 10–4 T)

= 26 × 10–2 m = 26 cm

ν = v / (2 πr) = 2×106 s–1 = 2×106 Hz =2 MHz.

E = (½ )mv 2 = (½ ) 9 × 10-31 kg × 9 × 1014 m2/s2 = 40.5 ×10–17 J

4×10–16 J = 2.5 keV.

4×10–16 J = 2.5 keV.